In January, an Arizona Congressman sent his social media followers a photograph of former President Barack Obama shaking hands with Iranian president Hassan Rouhani, a photo shared days after an American missile strike targeted and killed Iranian general Qassem Soleimani.

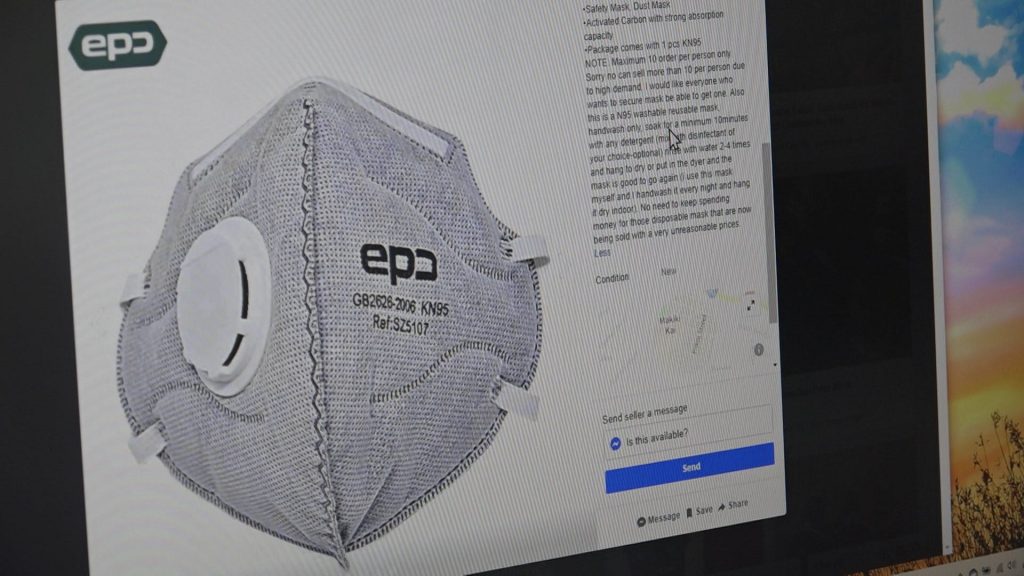

Nearly three years ago, an online headline blared an announcement that “Fixer Upper” co-star Joanna Gaines was stepping away from the television show to sell a new line of skin care products that she had created.

Last week, a 30-year-old video of Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders using racial and ethnic stereotypes while speaking to elementary school students in Vermont surfaced.

These news items were widely circulated to thousands on the internet, including social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

They also are totally false. Repeat, totally false.

The first was found to be two photographs combined to look like Obama and Rouhani physically met. The second was a business scam widespread enough that Joanna Gaines had to address it on her social media accounts. The third was a video of Sanders speaking about stereotypes to students, but with that crucial context edited out.

These days, good online advice might be “caveat lector”: Let the reader beware. Welcome to the disconcerting, if not downright scary world of fake news and disinformation where news that seems true and trustworthy on the surface instead may be calculated deception.

The global scale of such platforms as Facebook — 220 million American users in a nation of 331 million people — their ease of use and an unparalleled ability to reach individual readers make them attractive for organizations, businesses, parties, individuals and nations who gain through shaping perceptions.

Attention to the problem of online disinformation and fake news appreciably increased in the 2016 presidential campaign between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, one fought in part in such platforms as Facebook, Twitter and reddit and with messaging traffic from Russian trolls and bots deliberately muddling the situation.

Three years later, with little penalty for past abuses and with three years of President Trump’s labeling of critical news stories as fake news, political and academic observers believe 2020 may see even higher floods of misleading stories, distortions and outright fabrications in social media.

Mia Moody-Ramirez, chairman of Baylor University’s department of journalism, public relations and new media, sees the problem from multiple angles: training young journalists about accurate reporting and being savvy online, as well as a researcher into how social media is used.

The convergence of two social media trends — its increasing use as a source of news and its utility in expressing users’ opinions and beliefs — explain much about why it’s a logical target for those using disinformation to promote their cause.

At the same time, there’s a commercial incentive — profit — for businesses and advertisers to get viewers to their pages and ads. “People have to remember they make money that way,” Moody-Ramirez said.

Social media also shapes perceptions. The first to post an idea or viewpoint on a subject often can steer later discussion, even when the initial post is disproven or discredited. Less appreciated is how social media users can mistake their news feed and comment threads, crafted by software algorithms to reflect their likes and interests, as representative of their physical, more diverse communities.

“People’s feeds are very different,” she observed.

The journalism professor observed that her students, part of a digital-native generation, tend to be more aware of how online sites, phone apps and social media can be used and misused. Many use platforms such as Snapchat, Instagram or Pinterest that, due to smaller audiences or messaging structure, make them less preferred in disinformation efforts.

The swelling amount of false or distorted information presented online presents a challenge to professional journalists, noted Texas Press Association executive vice president Donnis Baggett, who added that may offer an opportunity for those news organizations to demonstrate their worth.

“It’s caveat emptor out there and because of that, your established news (providers) are the most credible ones out there,” said Baggett, a former Tribune-Herald publisher.

That said, there’s a role for readers to become media literate.

“You need to look at everything with a healthy skepticism. You need to know the difference between news and opinion,” he said. “Sometimes there’s more than two sides to a story, but you almost never hear more than two now.”

That healthy skepticism should be part of the job description for journalists, says Elon University journalism professor Amanda Sturgill, who formerly taught at Baylor.

Sturgill’s upcoming book “Detecting Deception: Tools To Fight Fake News,” set for a July 1, 2020 release, aims to give young journalists some pointers on employing that skepticism into fact-checking.

Much of what goes into fact-checking is standard practice for copy editing, but the ubiquity of online information and the speed at which it can spread makes verification and correction a challenge.

“Research shows that most people get their news through social media,” she said. “It’s when people are sharing bad information that it’s a problem.”

It’s not just journalists who have a need to identify and counter fake news. Combating rumors and fake news comes with the territory for Magnolia spokesman John Marsicano. Adding to the challenge is the internet’s instant, global reach; media competition; and the growing celebrity of the Gaines and their Magnolia empire, he noted.

“Today, obviously, there’s no shortage of information out there and there’s no shortage of ‘sources’ of information, either,” he observed. “There seems to be a growing disregard for accuracy. Instead, there’s a growing desire to be first.”

While outrageous headlines connected to fake or misleading stories were once largely limited to gossip tabloids, those headlines or their equivalent now appear online, steering curious viewers to a website to boost its traffic.

“It’s the ‘Five biggest secrets Chip and Joanna don’t want you to know’ clickbait,” Marsicano said. “It doesn’t even matter that anyone read the story. As long as you’ve clicked the link, that’s what they want.”

The 2017 scam on the fictitious Joanna Gaines skin care products, however, went far beyond clickbait.

“It was an extremely, extremely elaborate fake website. We’re talking federal-level crime,” Marsicano said, noting a similar scam had used the images and brands of actresses Halle Berry and Emma Stone.

Hundreds of people fell for it, even though no Gaines or Magnolia social media outlets or websites mentioned any sort of Gaines-approved skin care products.

“No one thought to see if this was verified,” he said.

Joanna eventually addressed the issue on her Instagram account and blog. Marsicano advised customers and online readers to check with official sources and representatives whenever they come across something that raises an eyebrow.

“If you don’t hear it from us, proceed with caution,” he said. “Don’t underestimate the power of your natural instincts . . . .I wouldn’t underestimate the efficacy of ‘just ask.’”

Chris Hoke works in local social media marketing and advertising with his company Social Media Cowboys. He finds fake news doesn’t impact many of his clients, particularly local ones, but notes a bit of common sense and context can go a long way in slowing its spread.

“You have to consider the source (of a news item) and stop assuming your side won’t do it,” Hoke said. “No one has the moral high ground on this.”

Hoke said the strong pull of confirmation bias — where readers or listeners put more weight into opinion or news they agree with, factual or not — causes many to look the other way when facts don’t support one’s opinion.

“You’re already looking for the answer any way you can get it,” he said.

Though disinformation may be increasingly commonplace online, Hoke said the tools to combat or slow it are in the hands of the typical online user: “A little generosity, a little research and a little mindful interaction.”

Journalism professor Sturgill would agree.

“I’m pessimistic about the situation, but I’m optimistic about people,” she said. “If people make an effort to be media literate and have a broader media diet, it helps a great deal.”

— Waco Tribune-Herald to www.wacotrib.com